Heinrich Hoffmann was born 138 years ago today on 12 September 1885 in Fürth, a large provincial city located to the north-west of Nürnberg. He was the only child of well established photographer Robert Hoffmann, who later joined a successful portrait studio in Regensburg with his brother, also named Heinrich. As a teenager Hoffmann was already exhibiting an innate talent in photography while helping out his father and uncle in the family’s shop, and he was even hired on as an assistant to Hugo Thiele, the official court photographer of the Grand Duke of Hesse in Darmstadt.

As a young man he moved to London in 1907, taking a job publishing art books under the apprenticeship of the most famous art photographer in Great Britain, Emil Otto Hoppé, in order to further hone his craft as a photographer. Two years later he returned to Germany and opened his own portrait studio in Munich at the age of 24.

During the First World War, Hoffmann served as a photographer in the Bavarian Army on the French Front. After the war he worked as a press photographer and published his first photo book ‘Ein Jahr bayrische Revolution im Bilde’ [Bavarian Year of Revolution in Pictures] in 1919.

On the 6th of April 1920 Hoffmann joined the NSDAP (membership card #427) and was immediately admitted into its inner circle. He had become a close and constant companion to Adolf Hitler by the time he took complete control of the party in 1921. Hitler intentionally avoided having his photograph taken in order to try and profit from selling the very first picture to be taken of him, but his plan was foiled by a reporter capturing his image at an outdoor rally in 1923. He named Hoffmann as his official photographer the very next day and no other photographer but Hoffmann was allowed to take pictures of Hitler. Heinrich Hoffmann’s official title within the party was Photo-Bildberichterstatter der Reichsleitung der NSDAP (official photographer of the NSDAP Reich Leadership). Thanks to the life’s work of Hoffmann, who estimates he took close to half a million photographs during his career, Adolf Hitler ended up being one of the most photographed personalities of the 20th century.

The cash strapped NSDAP opened its third Party Headquarters, after Hitler’s prison stint and his reestablishment of the party in February 1925, in a loaned space behind Heinrich Hoffmann’s office and photographic studio at Schellingstrasse 50 in Munich. The entrance was located in the courtyard behind the building and Hoffmann had a house in the back of his modest studio as well. The NSDAP headquarters remained here for six years until the move to the Brown House in January of 1931.

By 1939 Hoffmann was so successful that he had opened eleven branch offices for his photo business that included locations in Berlin, Vienna, Frankfurt, Paris and The Hague. Unlike most of the Nazi upper echelon, Hoffmann was quite worldly. Due to his time spent working in London he was fluent in English and he even maintained an office in England until the outbreak of the war. Adolf Hitler often visited Hoffmann’s home in the affluent Munich-Bogenhausen neighborhood, where he felt that he could relax away from his hectic political life and enjoy frequent large gatherings and the company of his family.

Hoffmann had first expanded his business in 1929 when he opened “Photohaus Hoffmann” at 25 Amalienstrasse, on a busy intersection with Theresienstrasse in central Munich. It was a very modern studio where formal portrait sessions were performed along with sales of cameras and other photographic equipment. At this time he also hired a shop assistant named Eva Anna Paula Braun, the 17-year-old daughter of a Munich schoolteacher. She first met Hitler here when he came in for a portrait session in late 1929. Two years later she became Hitler’s mistress and later his wife, just one day before both of them committed suicide during the Russian siege of Berlin in April 1945.

In 1932 Hoffmann further enlarged his firm of publishers, and expanded his shop on Theresienstrasse. At one time he had 300 employees and all exclusive rights to Hitler’s photos. Once the big money started coming in, the company split into two divisions, one which supplied editorial photographs, and the other which published photo-propaganda books. Hoffmann’s portraits and photographs, accumulating to close to 500,000 in total, were used for all sorts of official Nazi propaganda purposes and thoroughly charted the rise of the Third Reich.

His photographs were extensively published as postcards, posters, postage stamps, magazines and photo books. It was actually Hoffmann’s suggestion that royalties be paid for every single photo that was sold of Hitler, even for prints and on individual postage stamps, which made them both extremely wealthy men. The photographs continue to serve as a comprehensive visual record documenting the rise and legacy of the Nazi regime.

Hoffmann was Hitler’s most trusted friend and he often dined with Hitler at the Berghof or at the Führer’s favorite restaurant the Osteria Bavaria. Even when Hitler became Chancellor of Germany, Hoffmann still remained the only person authorized and trusted enough to take official photographs of him. Due to his exclusive access to the Nazi inner circle he adopted the title Reichsbildberichterstatter (Reich Picture Reporter) and his company “Heinrich Hoffmann, Verlag Nationalsozialischer Bilder” (Publisher of National Socialist Pictures) became the largest private company of its kind. Whether his subjects were gathered in packed beer halls, assembled in jammed auditoriums, or parading down crowded boulevards, the Nazis in all their pomp and finery were captured for all posterity before Hoffmann’s camera.

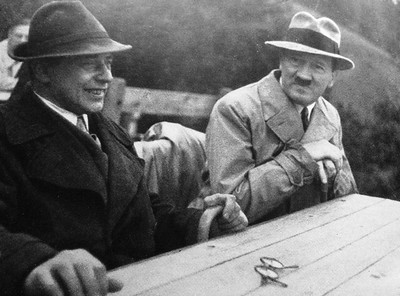

Heinrich Hoffmann at the Berghof taking photographs of Adolf Hitler out greeting the public. Being the official Party photographer he was always present. He shared a uniquely close and private relationship with Hitler, always in attendance to document every key event in the Nazi timeline.

Heinrich Hoffmann had disclosed to reporter Bernard Taper of the ‘New Yorker Magazine’ in an interview from prison in early 1950 that Hitler had not been an easy person to photograph. He couldn’t tell him how to pose, and when he wanted his photograph taken, his secretary would tell the photographer when and where to be, and he was expected to have everything ready and waiting when Hitler got there.

“Hitler would stride in, take his stance in front of the camera—you know, head stiff, chin drawn in, hand on his hip,” Hoffmann said. “Everybody knows the pose. He had only three public poses: one hand on one hip, a hand on each hip, and arms folded. Then he would announce, ‘I am ready. Take my photograph.’ And no photographer would have dared to suggest, ‘My Führer, the public is bored with that pose. Would you be so kind as to try another?’ ” Hoffmann laughed loudly at the very idea. “Earlier, he had had another pose—holding his riding whip in both hands—but he gave it up after Streicher, who also carried a whip, made a fool of himself by attacking an editor with it. Even I never tried to tell him how to pose, of course. But I always had my camera with me, even when I was just paying a social call. I’d watch him till I saw something I liked. Then I’d call out, ‘There! Hold it! Just like that!’

Adolf Hitler opened the House of German Art in Munich in 1937. At the same time the museum’s very first show was unveiled – the “Great German Art Exhibition.” It was the first of eight annual exhibitions that aimed to illustrate what Hitler defined as “German art.” The exhibited works were originally to be selected from a public competition. However a few weeks before the exhibition was to open, the appointed jury, which consisted of artists loyal to the regime—such as Adolf Ziegler, Arno Breker, and Karl Albiker—was abruptly dismissed by Hitler and the selection process solely left to the discretion of his personal photographer, Heinrich Hoffmann.

Hitler and Hoffmann stand in front of the “Porträt des Führers” by Fritz Erler, 1939. Displayed in Room 1 of the “Great German Art Exhibition” in 1939. The work was bought for 25.000 Reichsmark by Edoardo Dino Alfieri, the Italian Minister of Culture and Propaganda. Thirty-six paintings and busts of Hitler were displayed at the Great German Art Exhibitions from 1937 to 1944.

The artistic community felt that Hoffmann was grossly under-qualified for the role as the museum’s curator. Hoffmann’s answer to all of the ongoing criticism was that he knew exactly what Hitler wanted and what would most appeal to him. Although some of Hoffmann’s choices were also angrily dismissed from the exhibition by Hitler, he remained in charge of the selection process for all subsequent Great German Art Exhibitions. Hoffmann would go on to receive the honorary title of “Professor” on the 1938 Day of German Art. That same year he was also selected for the board that decided which confiscated artworks were deemed as artistically worthless and therefore condemned to destruction. Hitler personally inspected these “degenerate” pieces and ordered the burning of over 1,000 paintings in the courtyard of Berlin’s central fire station on 20 March 1939.

In 1939, Hitler named his ever loyal companion and confidante Hoffmann as Joachim von Ribbentrop’s special attache in Moscow to witness the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Ribbentrop and Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov. Stalin himself greeted the visitors, much to the Nazis’ surprise, as Stalin always avoided any interaction with foreign guests. His presence at the meeting showed how seriously that the Soviets were taking the negotiations. The pact guaranteed peace between the parties and was a commitment that neither government would aid or ally itself with an enemy of the other. In addition to the publicly-announced stipulations of non-aggression, the treaty included the ‘Secret Protocol’, which defined the borders of Soviet and German spheres of influence and gave Hitler the green light to invade Poland.

Heinrich Hoffmann toasting Stalin and his foreign minister Molotov after the signing of the non-aggression pact between Germany and the Soviet Union on 23 August 1939.

Even after the outbreak of the war Hoffmann continued to extensively publish picture books, posters, portraits and other highly circulated Nazi propaganda materials. His superb artistic talent and massive photographic portfolio was integral to the shaping of Hitler’s image and the continual crafting of the Führer persona. Hoffmann’s photographs were by far the most significant component of Hitler’s massive propaganda agenda to completely seduce and influence the German public.

Hoffmann’s first picture book, ‘The Hitler Nobody Knows’ (1932) was integral to Hitler’s early attempts to manipulate and control his public image. Hitler exclusively experimented with his persona through Hoffmann’s lens by posing for portrait sessions in business suits, uniforms, trench coats and even in lederhosen, the latter of which were banned and ordered to be destroyed in 1933. Early picture book publications showing images of Hitler hugging children, playing with dogs and feeding wildlife were successful in completely reinventing his image from a rabble-rousing street fighter to a warm and loving father figure solely dedicated to his country and his people.

The annual mail order catalogs produced by Hoffmann’s atelier were printed and disseminated in the hundreds of thousands. German citizens were encouraged to purchase and distribute the photographic propaganda that he produced.

Heinrich Hoffmann’s annual publishing catalog featured a wide range of propaganda material that extended from every possible formal portrait of Hitler and all of the top Nazi leaders, to informal photos of Hitler posing with children or enjoying outdoor recreational activities. The large listing of portraits, postcards, and photo books included other prominent figures such as Paul von Hindenburg, Benito Mussolini, Francisco Franco, Rudolf Hess, Hermann Goering, Joseph Goebbels, Baldur von Schirach, and the various Gauleiters. Formal framed portraits were also available for perusal and purchase in large showrooms located at all of Hoffmann’s shops across Europe.

Heinrich Hoffmann was a regular visitor to the Berghof, and his camera captured many scenes of both the social and private life Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun. Hoffmann frequently joined Hitler on his daily walks around the Obersalzberg area. One of his favorite trails was the Der Carl von Linde Weg, starting at the Platterhof Hotel and leading to a beautiful picnic area (shown below) that was located right next to the Hochlenzer Gasthaus. Here Hitler is joined by Heinrich Hoffmann on two separate occasions at his favorite picnic table overlooking the Königssee and Steinernes Meer.

Hoffmann visiting with Hitler out in the terrace of the Berghof:

In the early 1940’s Hoffmann began to lose much favor with Hitler for several reasons. Mainly because Hitler’s personal secretary Martin Bormann did not like him, and Bormann had gained complete control over who had access to Hitler. Another reason for Hitler’s growing disfavor was Hoffmann’s increasing struggle with alcoholism. He still managed to take the last known photograph of Hitler on 20 April 1945, Hitler’s 56th birthday. The photo was taken in the Führerbunker in Berlin and shows Hitler standing outside on the bunker’s terrace, surveying the damage caused by the fighting in the streets above. The photo was taken just ten days before Hitler committed suicide in the bunker with his wife Eva Braun.

Heinrich Hoffmann congratulates Adolf Hitler on the occasion of his 53rd birthday, which was celebrated at the Führerhauptquartier Wolfsschanze on 20 April 1942.

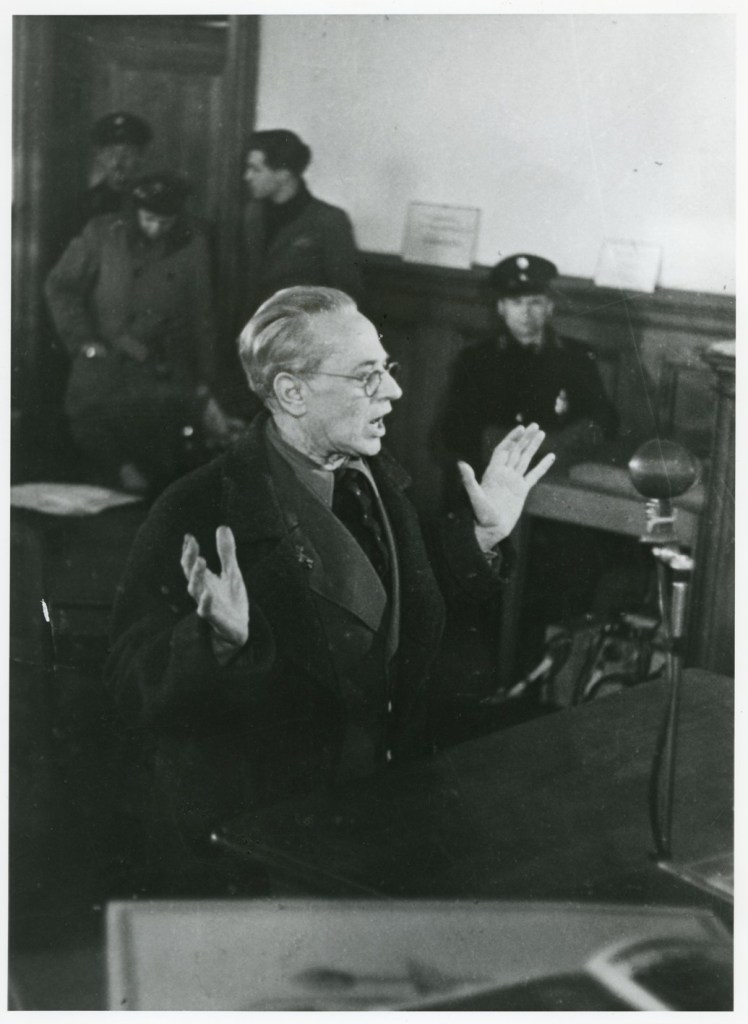

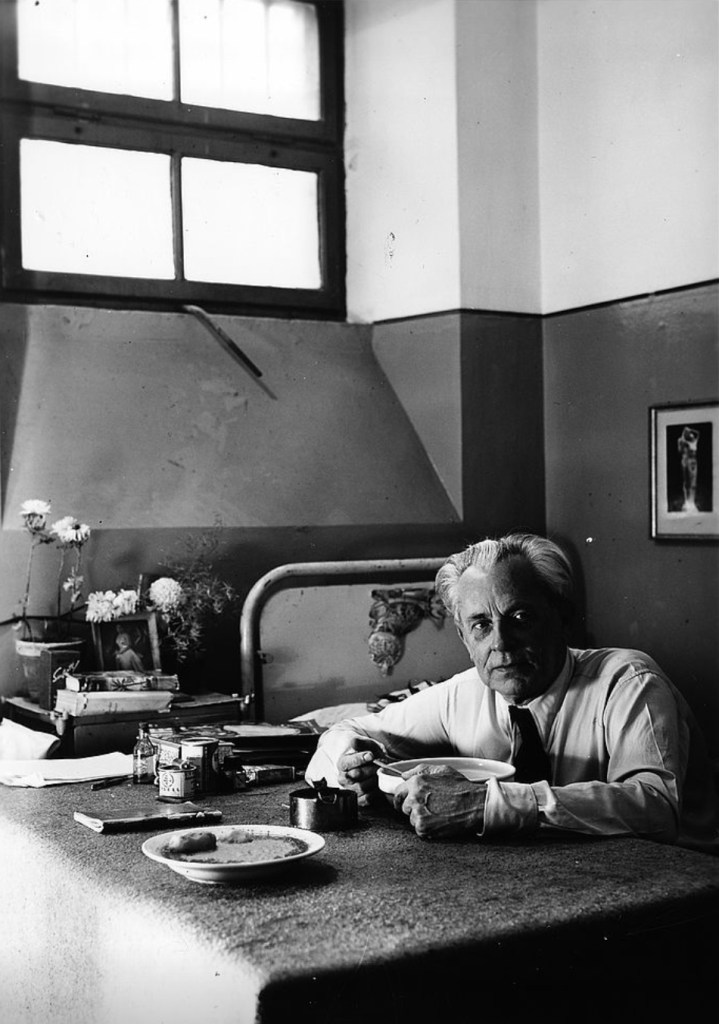

Heinrich Hoffmann figured quite prominently in the Art Looting Investigation Reports conducted by the Office of Strategic Service’s (OSS/precursor to the CIA) Art Looting Investigation Unit (ALIU). He was arrested by the United States Army on 10 May 1945 and had his entire fortune and art collection confiscated. He was later tried and sentenced to four years in prison for war profiteering. The army considered him a “major offender” in the Nazi art plundering of Jews as both an art dealer and collector. Werner Friedman referred to him one of the “greediest parasites of the Hitler plague.”

Hoffmann and his son had to sort through his entire confiscated photo collection in order to supply evidence for the Nuremberg trails. The “Historical Division” of the US Army then took over the archive and brought it to the USA in 1950. It was later transferred to the National Archives and Records Administration, where it remains to this day. The inventory, known as the “Hoffmann Collection” consists of around 280,000 image units, including glass plates and contact prints. The Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich also maintains a Hoffmann Photo Archive of 70,000 negatives and prints. It would be extremely rare that any book or documentary produced about Adolf Hitler or the Third Reich hadn’t pulled material from these collections.

Heinrich Hoffmann, the official photo correspondent of the Third Reich and Adolf Hitler’s constant companion, testifies in front of the tribunal in Munich on 9 February 1947.

Upon his release from prison on 31 May 1950, Hoffmann settled in the small village of Epfachin in southern Bavaria. Some of his assets were returned to him including much of his art collection. In 1954 a ten-part autobiographical series, “Hoffmann’s Tales”, was published in the weekly magazine “Münchner Illustrierte”. He also published his memoirs in 1955 under the title “Hitler Was My Friend” before he passed away just two years later on 16 December at the age of 72.