"We need a fellow at the head who can stand the sound of a machine gun. The rabble need to get fear into their pants. We can't use an officer, because the people don't respect them any more. The best would be a worker who knows how to talk... He must be a bachelor, then we'll get the women."

-Dietrich Eckart, founding member of the DAP, 1919

One hundred and two years ago today, on 29 July 1921, Adolf Hitler officially assumed leadership of the Nationalist Socialist German Workers’ Party. Hitler had joined the organization in September of 1919 and by early 1920 had swiftly risen up the ranks into a leading position. That January, he and party founder Anton Drexler had co-composed the party platform, which would remain in effect until the collapse of Nazi Germany in May 1945.

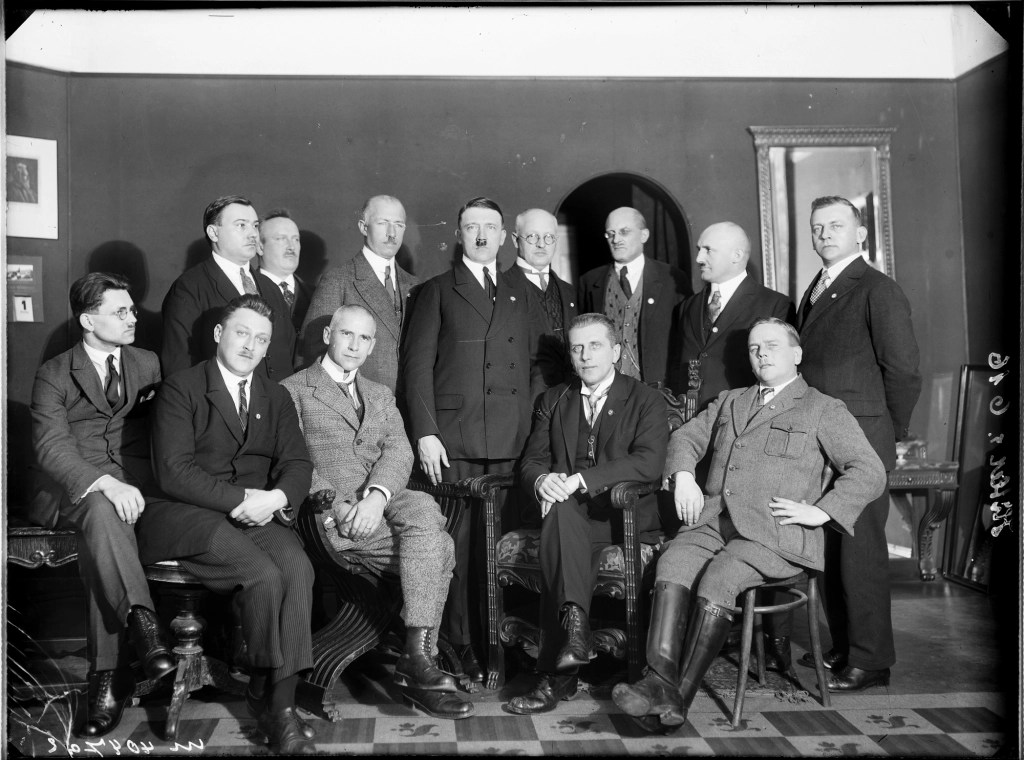

Adolf Hitler at the first meeting of the Austrian National Socialist Party in Salzburg, where he first revealed the swastika flag that he designed here at the Chiemseehof on 7 August 1920.

Hitler was unanimously elected chairman in July of 1921 after an ongoing power struggle with Drexler, who was then pushed aside and assigned the title “honorary chairman.” Under Hitler’s control, the Nazi Party grew into a mass movement that ruled Germany as a totalitarian state from 1933 to 1945. It was also at this particular July 29th party gathering, held at the Hofbräuhaus, that Adolf Hitler was introduced as Führer of the Nazi Party, marking the very first time that title was publicly used to address him.

Adolf Hitler in conversation with Victoria Melita of Russia in Fröttmaning on 15 April 1923. While in Germany, Victoria showed an interest in the Nazi Party, which appealed to her because of its anti-Bolshevik stance and her hope that the movement might help restore the Russian monarchy.

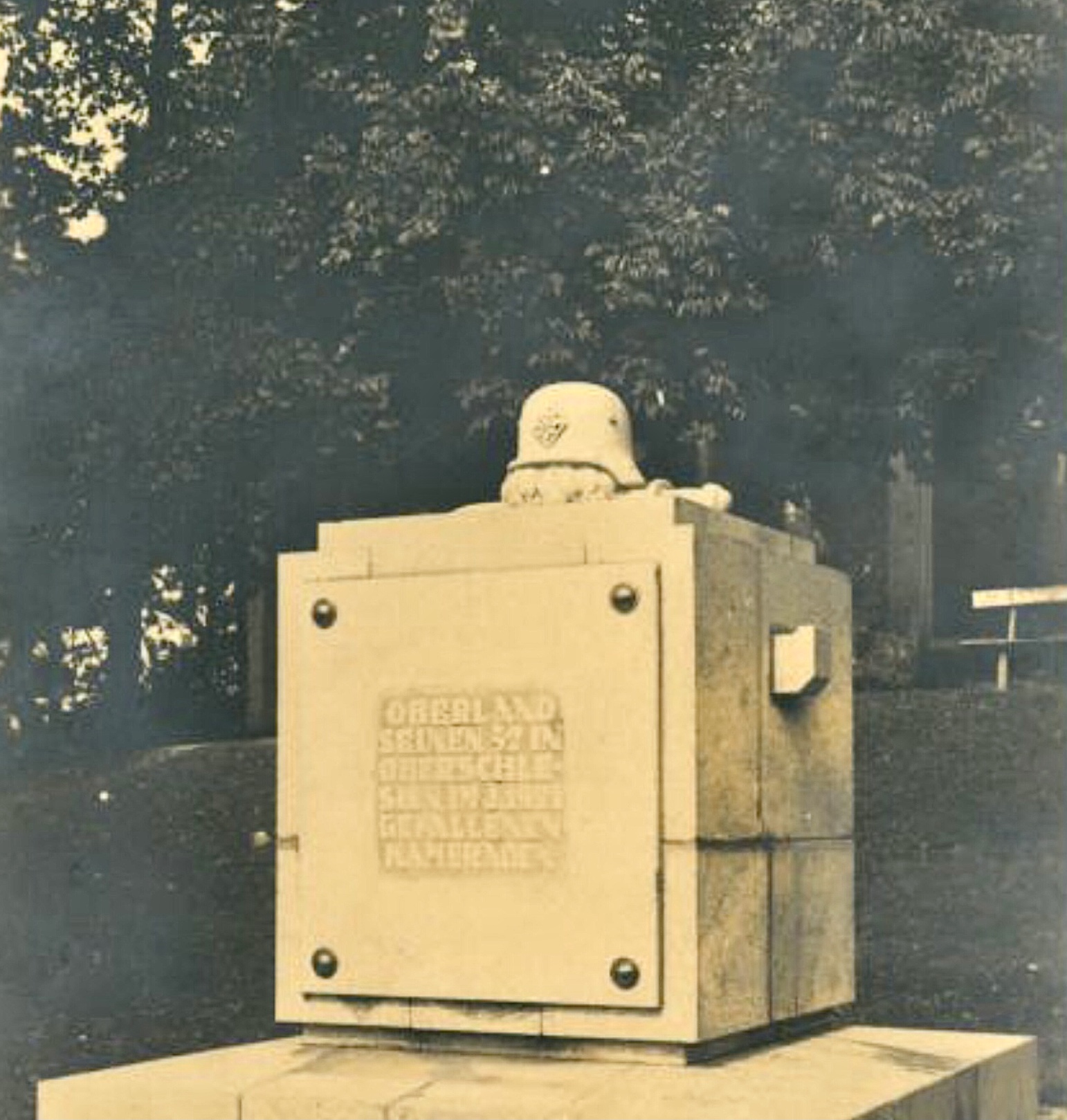

The Freikorps Oberland earned its reputation with an impressive victory in the 1921 Battle of Annaberg, displaying its prowess and determination to defend the fledgling Weimar democracy. Following its success, the Freikorps Oberland’s influence expanded further, particularly in Bavaria, where it ultimately became the core of the Sturmabteilung (SA). The SA, later known as the Brownshirts, played a critical role in the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in the 1930’s. Adolf Hitler visited the Oberland-Denkmal (Annaberg Memorial Monument) in Schliersee on 3 July 1927. The Annaberg Monument was located at the Vineyard Chapel and commemorated the Battle of Annaberg that occurred in Upper Silesia on 21 May 1921. The monument was erected at the vineyard in 1923 and it read “Freikorps Oberland – In memory of the 52 comrades who fell in the freedom fight around Oberfchlellen year 1921. They will be resurrected.” This particular monument was destroyed in 1945 but a new memorial was erected in the same location in 2021.

"Follow Hitler. He will dance, but it is I who have written the music.… Don’t weep for me: I shall have had more influence on the course of history than any other German.”

-Dietrich Eckart, on his deathbed, Christmas 1923

Party Rallies

The first “German Day” held in Nuremberg in 1923 and the subsequent Party Rallies of 1927 and 1929 firmly established the traditions for what became a yearly ritual for the National Socialist movement. These events were held annually from 1933-1938 and were intended to solidify the embodiment of the “Volksgemeinschaft” community spirit and to reinforce the “Führer” myth. Hitler and Goebbels’ mastery and understanding of mass psychology, stagecraft and visual imagery insured that the Nazi Party Rallies directly appealed to the spectators’ emotions rather than to their intellect and reason. The days were filled with a dazzling display of military maneuvers, parades, speeches, propaganda exhibitions, fireworks, concerts and opera performances.

The Party rallies were important propaganda events that Hitler began to formally organize in 1922. The first official Party Congress took place in Munich in January 1923, and the first Nazi Nuremberg rally took place later that same year in September. These early rallies were not particularly impressive or well attended, but as the party grew in size the rallies became much more elaborate and began to draw in larger crowds. They were meant to convey a unified and strong Germany under Nazi control. The rallies became an annual national event held in Nuremberg once Adolf Hitler rose to power in 1933.

When it was founded on 9 January 1919, the “German Workers’ Party” was one of dozens of right-wing nationalist and antisemitic groups that refused to accept Germany’s defeat in World War I, the abdication of Emperor Wilhelm II, and the founding of the German Republic. The Party was created and led by a railway locksmith named Anton Drexler, and like other populist groups, his German Workers’ Party was hostile to the social and political forces that supported parliamentary democracy—Social Democracy and the labor movement above all, but also Catholics, Jews and liberals. Between February and November of 1923, the party picked up 35,000 new members.

By the time of the Beer Hall Putsch in November 1923, total enrollment in the NSDAP was up to 55,000. Rumors that the National Socialists were planning a putsch had been circulating for over a year. Around noon on November 8th, Hitler marched into the offices of the Völkischer Beobachter, “with his riding crop in hand—the very picture of grim determination,” and told the astonished Rosenberg and Hanfstaengl: “The time to act has come… But don’t reveal a word of this to any living soul.” Hitler told them to come to the Bürgerbräukeller that evening, and to be sure to bring their pistols. The entire undertaking was very hastily improvised, which would be the main reason why the Putsch failed.

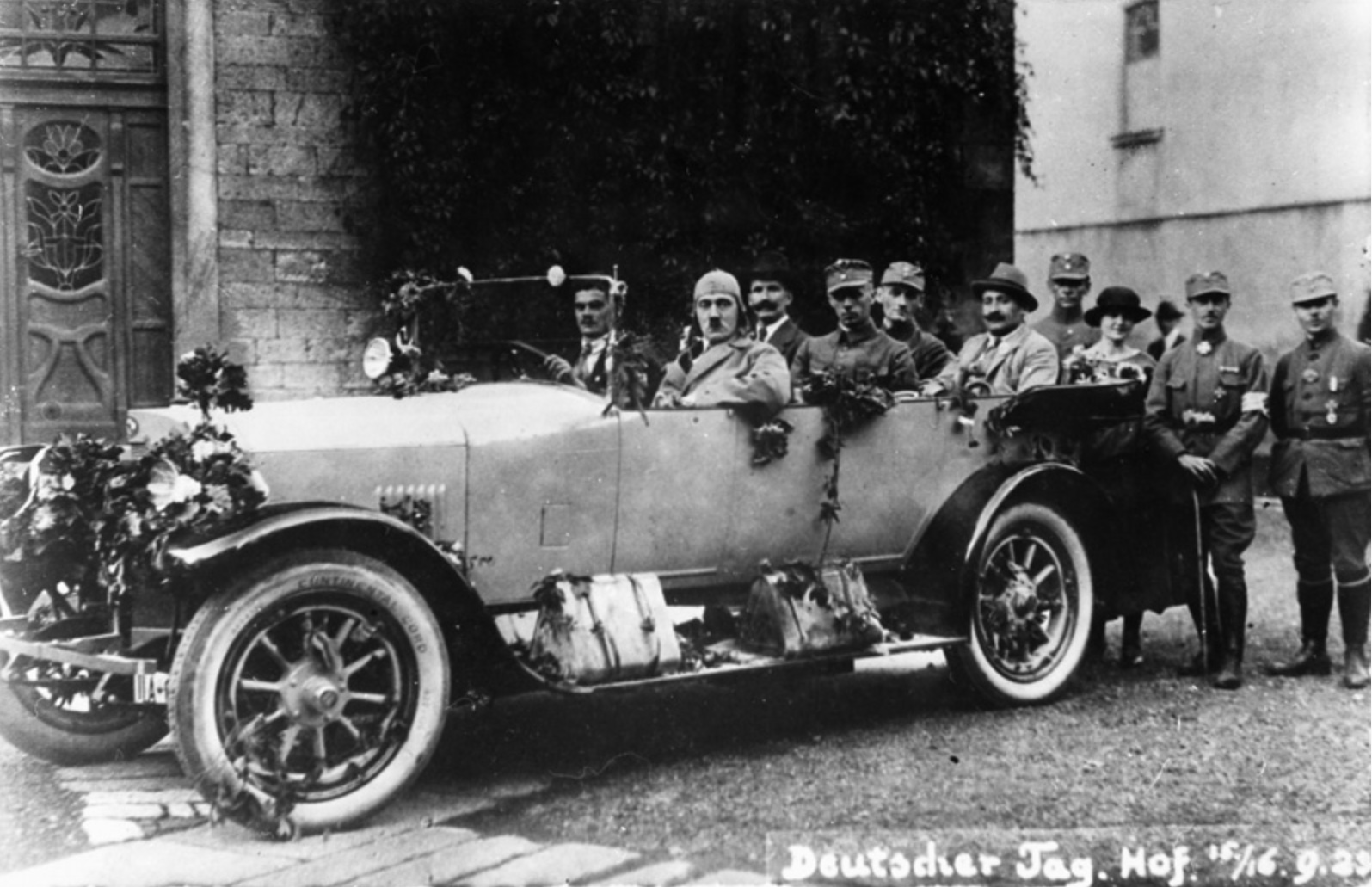

Starnberg German Day 1926

Adolf Hitler was the guest of honor at a special Duetscher Tag held in Starnberg in August of 1926. Organized by the town’s mayor Franz Xaver Buchner, Hitler was not actually allowed to speak at the rally as he was still under a two year ban from public speaking. Therefore the “big National Socialist rally in Starnberg” opened instead with a speech by Julius Streicher on 14 August 1926, followed by a parade through the city. Even though Hitler didn’t speak or arrive until late the next day, he still managed to leave a very big impression. Then 15 year old Helmut Sündermann, whom Hitler would later appoint as deputy press chief of the Reich government at the young age of 31, had his “awakening experience” on this occasion:

“But what remains unforgettable for me was the first glimpse of the man in a blue suit who silently laid a wreath at the Starnberg war memorial. Calmly, searchingly and demandingly, his gaze swept over the curious crowd. As he sat in the car, surrounded by men in brown shirts, hundreds of Starnbergers, as if obeying an inner compulsion, raised their right arms as a sign of greeting. Is it any wonder that the arm of a fifteen-year-old also stretched out like a vow?”

In November 1923, Franz Xaver Buchner took part in the Hitler-Ludendorff coup in Munich. After the ban of the NSDAP as a result of the coup, Buchner joined the Großdeutsche Volksgemeinschaft (GVG), a camouflage and replacement organization of the NSDAP. After the reestablishment of the NSDAP, Buchner was one of the founders of the Starnberg local group. He joined the party on 11 May 1925 (membership number 3.988). From 1925 to 1928 he headed the local group, then Buchner was an honorary district manager or district leader of the NSDAP in Starnberg. From 1928 to 1943, Buchner served as a Gauredner for Gau Munich-Upper Bavaria.

Hitler visits Karl Trutz, a friend of the Bechstein family, in the Villa Trutz at Hauptstrasse 67 in Tutzing before heading to Starnberg for the Deutscher Tag on 15 August 1926. Starnberg’s mayor Franz Xaver Buchner had organized a “German Day” to host Adolf Hitler as the guest of honor.

Starnberg’s mayor Franz Xaver Buchner had organized a special “German Day” in order to host Adolf Hitler as the guest of honor.

Just over 90 years ago, on 14 July 1933, Hitler’s government would declare the Nazi Party to be the only political party in Germany. The Communist Party and the Social Democrat Party had already been banned, and a new law also prohibited the creation of any new political parties. When the parliamentary elections were held in November, there was only one party on the ballot: the NSDAP, with Adolf Hitler as its leader. This collection of photos shows several significant events from the party’s formation in 1919 up until this law was passed.

The Bloody Night of Wöhrden

Adolf Hitler is shown below speaking at the funeral of the two victims of the “Bloody Night of Wöhrden” that occurred on 7 March 1929. A local group of the NSDAP had planned to hold a public rally on that day in Wöhrden, but the district administrator had forbade a rally. The National Socialists still convened in the town but converted the rally into a closed general meeting held in the Handelshof Inn. There were another 300 additional SA members in the “Zur Börse” Inn across the street. The Communist leader Christian Heuck arrived in Wöhrden later in the evening with 100 of his supporters. Marching provocatively past the two bars loudly singing the “Internationale” and chanting “Down with Hitler,” there was a bloody confrontation in which two National Socialists and one Communist were killed. Adolf Hitler personally exploited the violent death of the two SA men for propaganda and immortalized them as “martyrs of the movement”.

The Blutnacht von Wöhrden incident was publicized in a brochure widely distributed throughout the Reich in late March of 1929 titled “The bloody night in Wöhrden and its aftermath. An in-depth account of the communist murder attack and the Marxist police terror with numerous pictures and a speech by Adolf Hitler”. Below are three more photographs from Hitler’s moving speech that was delivered at the funeral of Otto Streibel in Albersdorf on 13 March 1929 that were featured in that publication.

The other victim in the deadly street battle was Hermann Schmidt, buried in the small village of Sankt Annen and whose funeral Adolf Hitler had attended the afternoon of 12 March 1929. Many years later Hitler paid another special visit to Hermann Schmidt’s grave on 29 August 1935, on his way to inaugurate the Adolf-Hitler-Koog. He also drove through the town of Albersdorf to visit Otto Streibel’s grave this same morning before stopping to have lunch with party comrade Schröder on his way to Adolf-Hitler-Koog.

Nazi Martyrs

Erich Jost also became an early martyr for the movement in the year 1929. Below are two photographs showing Adolf Hitler attending Jost’s funeral that was held in Lorsch on 9 August 1929. Jost was an SA Brownshirt that was killed by members of the Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold (Black, Red, Gold Banner of the Reich) which viewed the National Socialist Party as a threat to Germany. Erich Jost was stabbed in a brutal street battle that broke out during the Fourth Nazi Party Rally in Nuremberg. His funeral was also attended Reich Governor and Gauleiter of Hesse-Nassau-South, Jakob Sprenger. Jost was soon after made into a martyr for the Party.

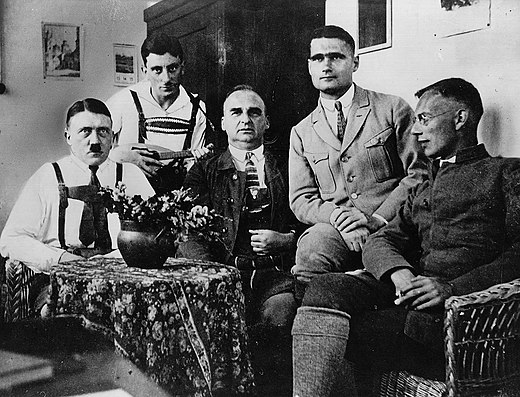

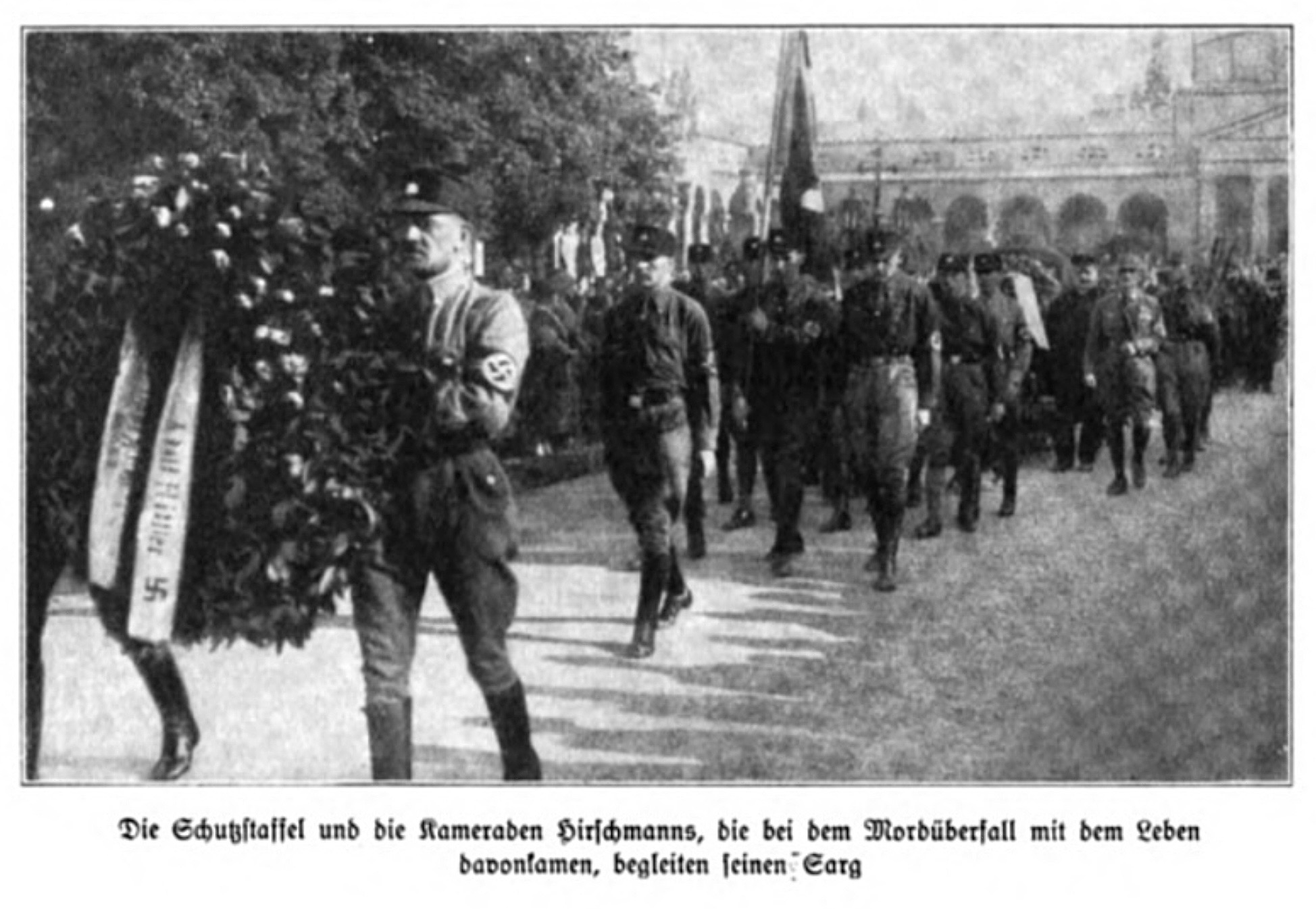

Two years earlier, another run-in with the Reichsbanner-Schwarz-Rot-Gold resulted in the death of a young shoemaker and member of the SA group “Hochland”. On the evening of 25 May 1927, Georg Hirschmann and five other SA men were chased down through the streets of Gisingen for over an hour by a few dozen political opponents, including members of the Reichsbanner-Schwarz-Rot-Gold, after a fierce verbal argument had erupted. After being brutally kicked and beaten with a wooden slat, Hirschmann suffered a severe concussion and passed the following day. Adolf Hitler attended his funeral on 30 May 1927 in the Ostfriedhof cemetery in Munich along with Rudolf Hess, Bruno Heinemann and Rudolf Buttmann, and delivered the eulogy. Two very rare photographs of Adolf Hitler and Rudolf Hess arriving for the ceremony are shown below.

The most significant of the Nazi martyrs was Horst Wessel, a young and ambitious member of the SA, shot at his home in Berlin by a group of communists on 14 January 1930. Joseph Goebbels was the first to recognize the propaganda potential by exploiting his murder: ‘A young martyr for the Third Reich’ as he wrote in his diary after receiving news of Wessel’s death. This was the beginning of the myth-making process that transformed an ordinary individual into a role model and hero for the Nazi movement. Thousands of people lined the streets of Berlin for Wessel’s funeral parade, and Goebbels himself delivered the graveside eulogy. His elaborate memorial site went on to became a place of pilgrimage, and the “Horst Wessel Song” became the official Nazi party anthem.

Adolf Hitler didn’t attend Wessel’s funeral held on 1 March 1930, a decision he based on Göring’s advice that the possibility of an attack on him in the heart of “Red Berlin” was far too great. Hitler did speak at Wessel’s gravesite three years after his death, on 22 January 1933, for the dedication of a memorial. Hitler called Wessel a “blood witness” whose song had become “a battle hymn for millions”. He said that Wessel’s sacrifice of his life was “a monument more lasting than stone and bronze”.

Funeral in Ebersberg for a member of the SA-Sturm 58, Josef Weber, killed in a brawl with members of the Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold. At the beginning of the 1930s, the Reichsbanner had 3 million members, the largest democratic military organization in the Weimar Republic. Adolf Hitler delivered Weber’s eulogy speech at the open grave on 19 June 1931. A street in Garmisch-Partenkirchen was named after him in 1933.

Senior Party Members

The social makeup of the Nazi leaders and party elites included individuals with such varied backgrounds as intellectuals, bureaucrats, aristocrats, farmers, war veterans, industrialists and middle-class civil servants. All social classes were represented to some degree within the party’s hierarchy, which aimed to overcome all class boundaries. This vast representation of classes and professions allowed the Nazi party to present itself as the Volkspartei (people’s party) that could overcome the social divisions and conflicts that shaped the Weimar Republic. Individuals who would have historically stood in political and social opposition to each another all found an ideological home within the ranks of the NSDAP.

The Berlin NSDAP Parteihaus in Gauleitung Berlin on 10 Hedemannstrasse, at the corner of Wihelmstrasse. This was listed as Joseph Goebbels address in the Berliner Adressbücher in 1933. Office of the NSDAP and the ‘Kampfblad Der Angriff’. ‘Der Angriff’ (“The Attack”) was the official newspaper of the Berlin Gau of the Nazi Party. Founded in 1927, the last edition of the newspaper was published on 24 April 1945. The newspaper was set up by Goebbels, who in 1926 had become the Nazi Party leader (Gauleiter) in Berlin, and the party provided most of the money needed to print the publication. The paper was originally created to rally NSDAP members during the nearly two-year ban on the party in Berlin. Adolf Hitler also visited this office on 14 July 1928. It was always referred to as the office on the Wilhelmstrasse.

The first meeting of the 107 NSDAP parliament members of the Reichstag took place in the Ebenholz Saal (Ebony Hall) of the Weinhaus Rheingold in Berlin on 13 October 1930.

On 14 July 1933, less than 6 months after Hitler assumed power as chancellor, Germany was officially proclaimed a one-party state. The Nazi party, which in the 1924 elections had received just 3% of the vote, was now the only legally mandated political party in the country, forbidding the formation of any other party. The Nazi Party had been born in an unassuming backroom of the Sterneckerbräu at Tal 54 in the Spring of 1919. This was where the Party had its first offices and where its early supporters had gathered. Adolf Hitler had joined in September 1919, and as a skilled orator soon rose to the top of the Party. Once Hitler became chancellor, the inn became a Nazi shrine and the NSDAP Party Museum was established there.

Anton Drexler, Gottfried Feder, Adolf Hitler, Hermann Göring, Hermann Esser, and Dietrich Eckart founded the NSDAP in the Sterneckerbräu in Munich. The Sterneckerbräu Beer Hall Museum of the NSDAP was officially opened on the 10th anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch on 8 November 1933.

Postcard produced to commmorate the 10th anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch showing Adolf Hitler at the opening of the Nazi Party Museum on 8 November 1933 in the Sterneckerbräu.